Technology Cannot Replace City Planning

We have to really figure out how to build cities, not just buildings.(Martha Schwartz, landscape architect)Nothing has disfigured the modern city more than the automobile. Unfortunately, the 21st century of city of the future concepts are still fixated on the automobile, except that the debate is now wrapped into technology. There is little evidence that a city shaped by high tech mobility would be any more inviting than the one we already have.

|

| Downtown Denver urban renewal for the automobile (Denverite) |

What the auto fixated build-more-roads-politicians of old lacked in fantasy is compensated by the futuristic ideas of techies like Elon Musk's who truly brings the auto to the mobile through autonomous electric cars and tractor trailers. The tech enthusiasts believe that they can do better than the old concrete and pavement guard because extra highway lanes would become superfluous with automated trucks and cars making existing roadways at least twice as efficient. But the past and future transportation visions share one common flaw: They are fixated on hardware, i.e. on vehicles and their needs, not on people and quality spaces. But cities are spaces, foremost which should people not vehicles. This may sound trite until one realizes that cities were actually never designed with people as the central focus. Before the automobile-centric city there was the production and shipping-centric city, and before that the city was foremost about the locus of real estate development, markets or defense. The art of architecture was mostly about buildings and an expression of power and much less about the city as a whole, i.e. about the spaces between buildings. In spite of nostalgia for old times life in cities was pretty miserable for most most of the time.

|

| Autonomous electric GM Bolt in Michigan (Wired) |

That is not to say that architects never thought about cities (ten urban diagrams can be found here) but only a few put the human into the center (such as Christopher Alexander). Recently the city has been the target for more sustainable and more resilient solutions. Certainly new technologies such as the autonomous vehicle will have a huge impact on cities, but just like the previous paradigms, they are not primarily human centric either. The AV won't automatically solve current urban problems of inordinate space attribution to mobility, pollution or inequitable access and mobility. Whatever efficiencies the AV promises may easily evaporate without a proper reorientation of policies.

Just as added lanes always induced additional mobility demand so will the prospect of additional capacity enabled by technology. The added demand, the additional sprawl and the new capacity will cause a previously unknown onslaught of vehicles pouring off the freeways ramps like water from a supercharged fire-hose creating chaos at the city "gates". Autonomous or not, fleet based or individually driven, truck, van or car, such an onslaught would do nothing for cities and their people or the public roam. Transit guru Jarrett Walker calls this the geometry problem.

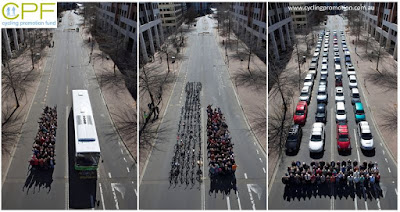

The scarcity of space per person is part of the very definition of a city, as distinct from suburbia or rural area, so the efficiency with which transport options use that space will always be the paramount issue. (Jarrett Walker)Neither additional freeway lanes nor Elon Musk's electric truck or his Tesla 3 trickling off its assembly lines at slow rates would change the fact that there is only so much space in a city and on a city street, even if they would be pollution free and drive themselves.

The Geometry problem

Some urbanists, therefore, hope for another technology to help cities: Vehicle sharing, assuming that an autonomous vehicle (AV) that isn't privately owned could free about a quarter of urban space by eliminating much of current parking. The automated fleet vehicles, so goes the thinking, don't park but go on to the next ride. But even if true, unintended consequences lurk right around the corner: What if those AVs would indeed not park but instead incessantly cruise around in search of the next assignment? Or fulfill errants people will invent especially for the vehicular bot. It is easy to imagine a whole lot of journeys that would only happen in a AV world. Freed from the unpleasantness of urban driving and looking for parking, what would stop people to send a driving bot out as personal servants? People-less bots of all kinds and sizes cruising around on streets, sidewalks or even flying overhead while getting flowers, pizza, Christmas trees or the kids from daycare could be the new urban nightmare. In that scenario it would become even more urgent to deploy "complete streets" policies to protect and assign the cherished and much debated "public roam."

While cities undoubtedly need to curb against such nightmares and embrace the positive aspects of the next generation of vehicle technology, the future of cities shouldn't be driven by automobiles or even bots, no matter in what shape they come, be it gasoline powered SUVs, Diesel trucks, sidewalk robots or electric share vehicles. A city crammed with AV's isn't intriguing nor is Elon Musk's dream of AV's dropping in elevator like contraptions underground to run in tubes like cash at the bank-drive-through. (a half mile or so of such a tube tunnel has already been bored underneath Los Angeles). If cities should no longer be shaped by mobility or technology, what should be the drivers?

|

| A beach in downtown Detroit (PPS) |

How exactly would a human centered city look like which is based on ordinary human activity?

For that the recent urban renaissance is actually illustrative. Already it was fueled by the desire for experience and a more multi-dimensional reality than the suburb can offer. As a result urban design made good progress in caring about the quality of not only buildings but the spaces in between and the ways how nature enters the city. The renaissance gave birth to new terms such as place-making and landscape-architecture indicating a focus on qualitative metrics which define the urban experience. Complete streets are more than giving all modes of mobility equal space, to do the term justice they must be joyful places where not only travel is facilitated but simply being in the space is joyful. Striving for a joyful experience of city as a pleasant space may sound like a bourgeois luxury because it was once limited to a small elite and its urban flaneur. A future in which cities are places of choice not only for commuters who come for work, not only for tourists who come to visit and not only for residents who live in posh neighborhoods rich with amenities but places where people of all walks of life want to live, work and play. In such a city the ability to cover a great distance in a minimum of time would become much less relevant than the actual sensual experience of being in a space. Such an experience is in contrast to the virtual experience that in large part has become the dominant way of people's daily existence. The city in the modern world of hyper-connectivity can only survive if it offers tangible real life qualities that virtual reality cannot match. Activities searching for or even requiring real life increasingly straddle the line between work and leisure and include meeting and experiencing other people through interaction or observation, as an active participant or as a passive observer in activities that could be enjoying food, games, work or simple leisure. But human centered design does not end there. Instead it builds social capacity and enlarges the number of residents who can enjoy their city instead of using it simply as a conduit for survival or to get somewhere else.

Once again, smart technologies can help to provide better access for more people, but technology is not an answer in itself. Technology must be screened for whether it furthers a good city, a better life for its residents and more equity. These qualitative metrics are much harder to apply than their quantitative siblings currently propagated under evidence based design and planning.

A city experienced by someone who is in it for enrichment looks different than a city traversed by someone in a hurry to get somewhere else. Last century's US cities were places which people who had a choice left behind after work , after visiting the theater, or going to a movie. Now that cities have become more attractive places to live, those who had been left behind in undesirable neighborhoods begin to be displaced from their central locations to the cheaper fringes.

|

| Benjamin Franklin Parkway, Philadelphia (the Oval) |

But this game of musical chairs is a zero sum game that is not only ethically unjustifiable, it is also economically wasteful. It has never been smart to segregate people and lock them in places of no opportunity. Interstate mobility is at record lows.

Some people aren’t moving into wealthy regions because they’re stuck in struggling ones. They have houses they can’t sell or government benefits they don’t want to lose. But the larger problem is that they’re blocked from moving to prosperous places by the shortage and cost of housing there. And that’s a deliberate decision these wealthy regions have made in opposing more housing construction, a prerequisite to make room for more people. (Emily Badger, NYT, 12/6/17)It has never been prudent use of resources to abandon whole swaths of the city and entire segments of the population nor has it ever been moral. It is a hard lesson that just when cities have become places which have begun to consider quality of life as a central tenet, economic inequality and neighborhood stratification have increased in most US metro areas, both in terms of income and race. The outcomes of living in cities have extreme variations from zip code to zip code. In Baltimore's Harlem Park life expectancy is 20 years below that of Baltimore's Roland Park. The retired US Senator Barbara Mikulski calls the fact that the neighborhood is more determinant to someone's health than their DNA zip-code determinism. Quality of life maps this same way for infant death rates, asthma, diabetes, income, home values, vacant structures, educational attainment, car ownership, food access or length of commute time.

These disparities have become so extreme in many US cities that the city as a system comes apart and a consensus on basic rules of life is hard to achieve. This has moved the question of what the city of the future should look like once again and with it the challenge for good urban design. It is no longer sufficient to make creative places, inviting urban landscapes and complete streets that aspire to more than bare functionality if these amenities are all concentrated in affluent areas in a replication of the city in which poor people and factory workers had to live in crammed quarters downwind from the pollution of the factories.

“A policy that aimed at reducing barriers to locational choice would outperform anything in the tax reform bill.” David Schleicher, law professor at Yale and writer about urban developmentWhat should shape a viable city of the future after the car, production, markets, and defenses as shape givers should be the equitable application of the art of city making across all sections of the city and all segments of its population.

Neighborhoods should not be defined by health outcomes and income but by the urban variety of cultures and the preferences residences express for living in a house with yard, an apartment, a quarter with bars or with art. All neighborhoods should cater to all human senses and allow access to parks, transit, permit safe walking and biking and the enjoyment of life.

Negative consequences of unequal neighborhoods are not limited to persons residing in low-income neighborhoods. Failing schools result in a less productive workforce. Crime and violence incur substantial costs in terms of enhanced security, policing, court systems, and incarceration. Poor health outcomes among those with no or publicly funded insurance drive up health care costs. The costs, financial and otherwise, of these outcomes are passed on to more privileged residents of metropolitan areas wherever they might reside (Paul A. Jargowsky, Professor of Public Policy Rutgers University, Economic Segregation in US Metropolitan Areas, 1970-2010)The affluent neighborhoods have become laboratories for creative and innovative urban models. In recent years the prospering parts of cities have demonstrated a million things about cities previously unknown. Among the new insights: that living in an apartment can be wonderful and allow plenty amenities, that abandoned factories can accommodate all kinds of wonderful new uses including innovation incubators as home for start-up companies, that parks can be created of abandoned elevated rail tracks of such high quality that they become a worldwide attraction, that old industrial buildings can become food markets or even schools, that once stinking covered streams can be opened up and become miniature waterfronts, that vacant lots can become pop-up gardens or food hubs, that bicycles can be shared, that bus arrivals can be seen in real time and tat a beach front is possible on the Seine in Paris and in Baltimore at the Inner Harbor. In short, there are so many things possible beyond the repertoire of the old city that cities one again shine as heavens of possibility. An yet.

Growing inequality in income fuels other disparities

What is needed is the insight that it is suicidal to deploy those new amenities only over half the city while the other half doesn't even supply elemental services needed for survival. While most cities are fiscally starved inordinate amounts of capital are sloshing through nefarious pipelines around the world. If the United States want to remain a place of opportunity, innovation and aspiration, capital and creativity has to be deployed now to fix the cities. It shall not be an excuse that this clarion call has gone out before as far back as Kennedy and Johnson. There are only so many opportunities in history before it is truly too late.

Klaus Philipsen, FAIA

Who is designing the 21st century city? NextCity

The future of urban innovations, Dartmouth

Urban Systems: The Challenge for the 21st Century, Designing the Urban Landscape To Meet 21st Century Challenges, a Yale Environment interview with Martha SchwartzMobility LAB: Resources and Playbooks on autonomous vehicles

APA Knowledge Base: Autonomous Vehicles

Nelson Nygaard: AVs and the future of Parking

.JPG)

Post a Comment