Better Schools Equals Better Communities - Or the other Way Round?

In his latest film "Where to Invade Next?" the filmmaker Michael Moore asks Finnish students and their teacher where Helsinki's best schools are located; he receives blank stares. A teacher finally enlightens Moore that in Finland all schools are the same, which means equally good. (Finnish student performance usually ranks #1 in international comparisons). No need for parents to shop around for schools before buying or renting a house or apartment. If the schools are equal it should follow that the differences between the Helsinki neighborhoods would also not be nearly as stark as, say, Baltimore, where life expectancy varies as much as 10 years within a few miles. Finnish schools, not being dependent on property taxes, don't have to rise and fall with their surrounding community.

By contrast, in the US the fate of schools and the community are intertwined on many levels. One of them financial. The denser and the poorer a community, the less money per student that can be raised through property tax. In large US cities schools perform much below their suburban counterparts and are seen as the albatross around the neck of cities, preventing them from attracting young families with children. School performance is the worst in poor communities with graduation rates far below and drop-out rates far above global standards.

Even in comeback cities public schools perform badly except for a few cloistered away in expensive enclaves of town propped up by wealthy sponsors, same for some spectacular magnet schools drawing students citywide and without district boundaries, such as the Baltimore School for the Arts.

As a result, contemporary education-fixated urban parents either pay a fortune for private schools or live in the suburbs. Education researchers on all levels are pulling their hair out trying to crack the tough nut of the urban school problem.

In that cycle of misery it hardly matters if it really is the school that is failing the city or not rather the city which is failing its schools. How can schools thrive in places where parents siphon all talent from the public school system, and how should cities thrive if their schools fail to attract the educated and upwardly mobile?

Ideas on how to break through the conundrum are plentiful, including a dizzying array of education models and organizational forms such as public, charter and contract schools, academies and magnets. Many of these concepts actually loosen the ties between community and school by eliminating the geographic restrictions that were in place for the traditional neighborhood school.

Educators pin their hope to the various pedagogies and models depending on their own believes. Urban planners hope improved student performance will convince more parents to stay in any given neighborhood or even attract the classic family with children to move into the city. Politicians strive for more control over schools. (In 1995 Chicago's Mayor took over the local schools, in 2016 at least one mayoral candidate proposes the same for Baltimore). It is astounding, then, how little the various sides actually collaborate.

In spite of an ever expanding expectation what schools should or could do in the community beyond providing a decent education and in recognition of the twisted entanglement between community and school, the idea of pooling large public investments in schools with public investments in the surrounding community, seems obvious. Alas, school planning and city planning remain strangely disconnected.

In the $1.0 billion quest of turning Baltimore City schools around, one can find the term "community school" a lot as part of the effort of creating "the 21st century school". Community school is such a popular term there is even a "National Coalition for Community Schools". They define the term this way:

Beyond that and in the context of the large 21 st Century Schools renovation project Baltimore City adopted an "Inspire" initiative, Investing in Neighborhoods and Schools to Promote Improvement, Revitalization, and Excellence which "will focus on the quarter-mile surrounding each school to leverage the investment in the school and enhance the connection between the school and the neighborhood. Plans will articulate the community’s vision for guiding private investment as well as identify specific, implementable public improvements in areas such as transportation, housing, and open space to improve the surrounding neighborhood so that it can better support the school."

By contrast, in the US the fate of schools and the community are intertwined on many levels. One of them financial. The denser and the poorer a community, the less money per student that can be raised through property tax. In large US cities schools perform much below their suburban counterparts and are seen as the albatross around the neck of cities, preventing them from attracting young families with children. School performance is the worst in poor communities with graduation rates far below and drop-out rates far above global standards.

Even in comeback cities public schools perform badly except for a few cloistered away in expensive enclaves of town propped up by wealthy sponsors, same for some spectacular magnet schools drawing students citywide and without district boundaries, such as the Baltimore School for the Arts.

|

| summer program in the Henderson Hopkins library (photo: ArchPlan) |

As a result, contemporary education-fixated urban parents either pay a fortune for private schools or live in the suburbs. Education researchers on all levels are pulling their hair out trying to crack the tough nut of the urban school problem.

In that cycle of misery it hardly matters if it really is the school that is failing the city or not rather the city which is failing its schools. How can schools thrive in places where parents siphon all talent from the public school system, and how should cities thrive if their schools fail to attract the educated and upwardly mobile?

Ideas on how to break through the conundrum are plentiful, including a dizzying array of education models and organizational forms such as public, charter and contract schools, academies and magnets. Many of these concepts actually loosen the ties between community and school by eliminating the geographic restrictions that were in place for the traditional neighborhood school.

Educators pin their hope to the various pedagogies and models depending on their own believes. Urban planners hope improved student performance will convince more parents to stay in any given neighborhood or even attract the classic family with children to move into the city. Politicians strive for more control over schools. (In 1995 Chicago's Mayor took over the local schools, in 2016 at least one mayoral candidate proposes the same for Baltimore). It is astounding, then, how little the various sides actually collaborate.

In spite of an ever expanding expectation what schools should or could do in the community beyond providing a decent education and in recognition of the twisted entanglement between community and school, the idea of pooling large public investments in schools with public investments in the surrounding community, seems obvious. Alas, school planning and city planning remain strangely disconnected.

|

| The portion of school funding coming from property taxes increases |

In the $1.0 billion quest of turning Baltimore City schools around, one can find the term "community school" a lot as part of the effort of creating "the 21st century school". Community school is such a popular term there is even a "National Coalition for Community Schools". They define the term this way:

A community schools strategy is a collaborative leadership approach designed to ensure that every student graduates from high school ready for college and/or career and prepared for a successful life as a family member and citizen. It offers a vision of schools, communities, and families linked in common purpose.Baltimore has its own Community Schools Initiative since 2005 which now claims that 20 schools in the city are "community schools", where

Through partnerships and coordinated services, Community Schools remove barriers to student and family success and deepen the experience of all its community members (website).Non-profits in Baltimore maintain that true community schools exist only where the non-profit sector really stepped up to provide full "wrap-around services" to students and their families to account for the full set of deficiencies in Baltimore's deeply segregated school system. As an example of the full extent of such services they point to the Benjamin Franklin High School in Baltimore's Curtis Bay neighborhood where a "community site coordinator" manages no less than 19 non teaching community service people, all not employed by the school system but paid through United Way and other non-profits.

Beyond that and in the context of the large 21 st Century Schools renovation project Baltimore City adopted an "Inspire" initiative, Investing in Neighborhoods and Schools to Promote Improvement, Revitalization, and Excellence which "will focus on the quarter-mile surrounding each school to leverage the investment in the school and enhance the connection between the school and the neighborhood. Plans will articulate the community’s vision for guiding private investment as well as identify specific, implementable public improvements in areas such as transportation, housing, and open space to improve the surrounding neighborhood so that it can better support the school."

A safe and stable neighborhood is fundamental for providing students and families with a healthy living environment, where children are more likely to attend school and have better outcomes. (INSPIRE)It may be necessary to remember that the concept of community schools is far from new. It goes almost as far back as mandatory public schools themselves, at least as far as to the late 1800s in Chicago. Later the concept was amplified by the American philosopher John Dewey who studied at Johns Hopkins in Baltimore and in 1902 spurred a whole movement that declared schools to be social centers in a widely published address:

“The conception of the school as a social centre is born of our entire democratic movement. Everywhere we see signs of the growing recognition that the community owes to each one of its members the fullest opportunity for development.”In 1913 over 70 cities in 20 states reported having such community schools in place, mostly characterized by allowing communities to use the schools as facilities far from the original teaching purpose. Uses include local health offices, art galleries and community libraries. All of these are back in the discussion right now. The community schools or neighborhood schools movement went through ups and downs during the last century and persisted at least until the national Neighborhood Schools Act of 1974 which sought:

"to provide a demonstration grant to local schools...to enable local schools to upgrade the education offered ...to such a degree that the educational deprivation, which many believe to persist in our schools today, would no longer exist" (source)Fast forward to current days: While few would doubt the close linkage between school and community or that it "takes a village to raise a child", it is equally obvious that weak communities cannot easily lift weak schools or vice versa. The refrain from teachers, that they don't have the means to meet all those expectations has persisted as well. Schools and cities, therefore were on the lookout for an element of strength to break this "catch 22" condition.

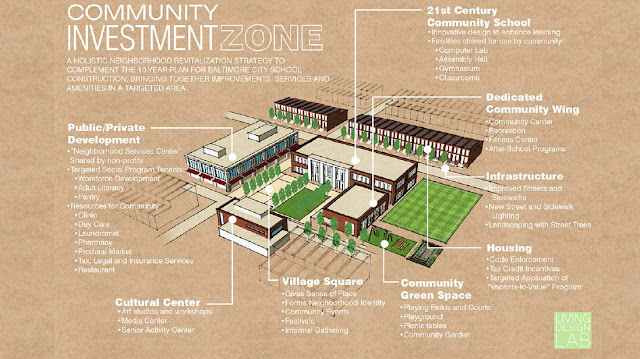

|

| The diagram of a school investment zone (Davin Hong) |

Strong academic institutions immediately come to mind as potential rescue candidates, especially those which are located in challenged urban areas, a frequent condition:examples include Temple University in North Philadelphia, Indiana University-Purdue in Indianapolis (IUPUI) or Johns Hopkins in East Baltimore. A group of authors writes in the Peabody Journal of Education in November 2013:

Because colleges and universities are often underutilized anchors of resources

in communities, coordinated alignment of K-12 and higher education goals can create a seamless pipeline of educational attainment for communities challenged to produce high academic achievement.

Higher education’s engagement with community schools further helps to address the whole child and their families in K-12 education by expanding the opportunities for the students and community to access necessary support services. (source)

This gets us back John Dewey and to Johns Hopkins as an anchor. The famous university whose Bloomberg School of Public Health has been active in developing countries on far away continents rediscovered as recently as 2005 the idea of the community school and sought to implement it right in front of its own door steps in the East Baltimore community of Middle East.

This entire community had been slated to become one of the nation's largest urban renewal projects, spearheaded by a strong anchor institution and the notion of re-building from strength which was promoted by then Baltimore Mayor Martin O'Malley.

Disregarding the fact that two public schools in the area had been slated for closure due to shrinking enrollment, Hopkins, the East Baltimore Development Inc (EBDI) and the Casey Foundation embarked on building a brand-new school branded as a community school and early anchor of the envisioned rebirth of the neighborhood.

I have written about the EBDI effort and the new school which is open and running for several years in blog essays about schools as placemakers or Hopkins as an anchor (Building from strength). Those articles brought Erkin Özay to my office, a Harvard educated urban researcher at the University at Buffalo who is compiling "a broad set of parameters impacting the conception of contemporary public school environments around this [Henderson Hopkins school] central case". Pulling a bunch of materials from my archive to assist the story of EBDI and the new community school, motivated me to enlarge my previous observations about the Hopkins-related urban renewal, Middle East and the role of schools in revitalization in this article.

In the October of 2005 the school idea was described in these words:

In the October of 2005 the school idea was described in these words:

The East Baltimore community—home to the Johns Hopkins Medical campus—is deeply troubled. Many residents live in substandard housing and face serious problems, from drug-related crime to high rates of unemployment. Fewer than 50% of area school children finish high school, and less than one-third of these graduates continue their education. But dramatic change is on the horizon. Work is underway on one of the nation’s most extensive urban revitalization efforts. The East Baltimore Revitalization Project will invigorate the streetscape with new housing and businesses; boost the economy with the creation of a Life Sciences and Technology Park and job training opportunities; and improve residents’ health and social well-being with an intensive program to assess needs and provide social and medical services. Critical to the enduring success of this ambitious revitalization effort is an innovative, comprehensive educational initiative proposed by Johns Hopkins, Morgan State University and East Baltimore Development, Inc. (EBDI). This integration of education programs and reforms builds on a strong existing partnership between the two universities and on lessons learned from revitalization projects in other cities. [.... ] The combination of economic, social, and housing revitalization at the core of the East Baltimore Revitalization Project will provide a community infrastructure that is critical to the success of meaningful urban education reform. The unique approach we propose—integrating a comprehensive educational initiative into the Revitalization Project—has great potential to transform the future of East Baltimore citizens, to improve the quality of education throughout Baltimore City’s public schools, and to provide a new national model for urban education reform.

In those lofty goals one can see finally the link between urban planning and education realized. In 2016, have these goals been achieved?

The school occupies 7 acres against the Amtrak rail line, boasts a large solar array, accommodates early childhood to grade 8 students, has a unique architecture and provides plenty community access and programming. Carefully programmed by competition advisor Isaac Williams and executed by competition winner Roger Marvel Architects, the school responds architecturally to the surrounding community, accommodates the school programmatically and admits students of the community preferentially. Its curriculum and pedagogy is influenced by Johns Hopkins and the historically black Morgan State University. In a 2013 discussion panel about "Edgeless Schools" Williams described the library as

"not only place for knowledge from outside the community but also a place for knowledge of the community from inside the community.Make each child feel that it was part of a community"

Vince Lee, the project manager at Roger Marvel conceded that it was hard to "build a community school where no community is left" alluding to the fact that the phase 1 revitalization had demolished every last house that once stood and relocated every family in it in an area that had made up a good part of the Middle East community. The actual realized library was designed by Srygley Architects and funded as a separate element by the Weinberg Foundation. Local architects complain that the school was way too expensive to serve as a plausible model for the Baltimore 21st century school initiative while the principal points to a renovation effort that had already been launched to mitigate some issues Roger Architects blame on value engineering.

The biggest setback came with the great recession which slowed the envisioned redevelopment effort even while the school went forward as planned. Many lots in Phase 1 still remain vacant, there are new bio-tech, retail and office facilities, new affordable and market rate housing was constructed and as part of Phase 2 a good number of rowhouses have been renovated.

The spirit of a complete community has yet to emerge and as such the school with its successful collaboration of anchor institutions, the public school system and the redevelopment agency is less a school of the community and more one in search of a community. Community and school are too entangled to give up. Cities across the country need to continue to pursue, refresh and fill with meaning the old dream of the community school unless the concept of school becomes entirely obsolete in the age of the Internet.

The biggest setback came with the great recession which slowed the envisioned redevelopment effort even while the school went forward as planned. Many lots in Phase 1 still remain vacant, there are new bio-tech, retail and office facilities, new affordable and market rate housing was constructed and as part of Phase 2 a good number of rowhouses have been renovated.

The spirit of a complete community has yet to emerge and as such the school with its successful collaboration of anchor institutions, the public school system and the redevelopment agency is less a school of the community and more one in search of a community. Community and school are too entangled to give up. Cities across the country need to continue to pursue, refresh and fill with meaning the old dream of the community school unless the concept of school becomes entirely obsolete in the age of the Internet.

Klaus Philipsen, FAIA

edited by Ben Groff, reference to Ben Franklin School added 3/5/16 . Reference to the New Yorker article added 3/6/16

Links:

A list of resources for the relationship community and school

Building Mutually-Beneficial Relationships Between Schools and Communities (Community Dev. Institute)

Baltimore City Inspire Program

Building Schools, Building Communities (Davin Hong Opinion Piece Baltimore SUN)

The Enduring Appeal of Community Schools (a historic overview in American Educator, 2009)

Time Magazine 1972, Education: Who Pays the Bill?

The New Yorker: Learn Different (3/16)

edited by Ben Groff, reference to Ben Franklin School added 3/5/16 . Reference to the New Yorker article added 3/6/16

Links:

A list of resources for the relationship community and school

Building Mutually-Beneficial Relationships Between Schools and Communities (Community Dev. Institute)

Baltimore City Inspire Program

Building Schools, Building Communities (Davin Hong Opinion Piece Baltimore SUN)

The Enduring Appeal of Community Schools (a historic overview in American Educator, 2009)

Time Magazine 1972, Education: Who Pays the Bill?

The New Yorker: Learn Different (3/16)

.JPG)

Post a Comment